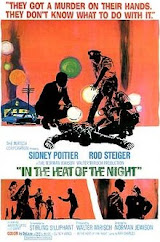

Reflections

on “In the Heat of the Night” (1967)

Directed

by Norman Jewison

Screenplay

by Stirling Silliphant

Based

on a novel by John Ball

Starring

Sidney Poitier, Rod Steiger, Lee Grant and Warren Oates

Industrialist Phillip

Colbert was due to invest a small fortune in the construction of a factory in

the small town of Sparta in the southern American state of Mississippi, but his

dead body is discovered in the street late one night by police officer Sam Wood

as he is doing his rounds. While seeking the person responsible for this crime,

Wood checks the local train station and comes across a black man waiting for a

connecting train. The colour of his skin appears to be reason enough to arouse

Wood’s suspicions and Wood arrests the man who, answering a few simple

questions from police chief Gillespie, reveals he is Virgil Tibbs, a homicide

detective in Philadelphia. Gillespie verifies this, considers him above

suspicion and, angry and frustrated, declares he is free to go.

These opening scenes,

embellished by a wealth of visual detail and strong characterisation, are

sufficient in themselves to underline the consequence of misguided and hasty

conclusions based on prejudice and racism. However, this is only the beginning

of a tale whose murder plot may be viewed as little more than a device to

explore underlying themes of racism, justice, principle, social justice and

friendship, achieved in good part through a study of the characters of Tibbs

and Gillespie and their burgeoning if somewhat forced relationship.

Police chief Bill

Gillespie has many characteristics in keeping with his upbringing and his

social environment, but he is a fundamentally good man who is perhaps out of

his depth. He cares about his position and seeks to protect the inhabitants of

Sparta. He takes responsibility seriously and appears to be aware of the

shortcomings of his department and staff. Gillespie tries to set standards but

seems to be fighting something of a losing battle as several officers are complacent

and idle, though they do not appear to be corrupt or malicious, leading to

frustration for Gillespie and displays of short temper and anxiety or

nervousness as he tries to exercise control but finds no real solution to his

problems.

Gillespie is not

complacent and is aware of his own limitations and perhaps even his prejudices

which he is willing to try to rise above.

He is unaccustomed to

being tested professionally and he recognises a murder investigation is

probably beyond his scope – he is used to minor infringements of the law and

has a relatively simple or blinkered view of procedure. He lacks sophistication,

instruction and experience but he is honest, direct and firm but fair. He is

certainly able to recognise the valuable contribution Virgil Tibbs can bring to

the investigation even if it hurts his pride and he is uncomfortable with what

he regards as Tibbs’s haughty involvement.

Gillespie’s intensity and

his determination to question and gently challenge traditional environmental

and social outlooks and attitudes, until now focused on the complacency and

attitude of his staff and already the cause of frustration and loneliness, is

brought to a head by the arrival of black detective Virgil Tibbs. This event

will put Gillespie’s underlying and perhaps even subconscious sense of principle

to the test and will bring about something of an evolution in his character.

Virgil Tibbs works in

Philadelphia and his big city background suggests he is accustomed to a broader,

more liberal and tolerant outlook than that displayed by his fellow police

officers in Sparta. Tibbs is reasonable, intelligent and educated, and he is

invited by his superior to share his skills and prowess with those colleagues

in Sparta who are willing to dismiss him based merely on the colour of his

skin.

He investigates using evidence,

facts and scientific knowledge, jumping to no hasty or unsubstantiated

conclusions, unlike his fellow police officers in Sparta, but he is treated

with scant regard and respect due purely to his ethnicity. Unaccustomed and

tired of this misplaced professional and personal antipathy, Tibbs decides to

leave Gillespie and his officers to their own bumbling conclusions, though he

insists on passing on essential evidence to higher authorities to ensure

justice is done.

It is at this point that

Gillespie is first put to the test. He knows he needs Tibbs and his expertise

and he is willing to put principle above self-regard, position and the local

mindset to solve Colbert’s murder. He also applies intelligence and a keen

understanding of human nature in his attempt to persuade Tibbs to stay. He

appeals to or challenges Tibbs’s vanity and a natural desire for retribution by

pointing out the satisfaction Tibbs will derive from proving himself superior

to those who have treated him and his conclusions as unworthy of consideration,

a challenge Tibbs reluctantly recognises and accepts.

At one point, Tibbs

extends this frame of mind and displays personal prejudice and a blinkered view

not entirely dissimilar to that shown by the local police as he is determined

to find evidence to support his desire to depose a local businessman whose

wealth has been built on the backs of black employees and who displays

condescension toward African-Americans while also displaying immense pride,

arrogance and a sense of superiority. Gillespie is quick to point out this

chink in Tibbs’s armour of apparent infallibility and reason and his human

desire for retribution, summed up by Tibbs’s historic retaliation when he is

struck by the businessman, and he reminds Tibbs, almost ironically, of the need

for a solid case built on evidence and fact.

Tibbs may be feeling somewhat

overwhelmed and is left a little out of his depth as he comes face to face with

blatant, vicious and unreasonable racism which has evoked resentment and

diverted him from the path of reason and truth, while Gillespie’s historically

prejudiced and biased mind has been focused on evidence, fact and deduction by

the reasonable and intelligent Tibbs. It seems that in these circumstances each

man finds direction and benefit from the other’s presence and input.

Tibbs solves the murder

case after further focused investigation and he and Gillespie end up sharing a

drink and a revealing conversation in Gillespie’s apartment. It transpires

these apparently very different men have much in common from a personal and

social perspective, though Gillespie reacts badly when Tibbs offers a well-intentioned

sympathetic comment which perhaps trespasses into the realms of familiarity and

friendship. Gillespie interprets this as pity rather than friendship and closes

down the conversation.

It appears that each has

focused on career and professionalism to the detriment of building a network of

friends and relationships and while each is willing to take steps toward

friendship, neither is socially skilled enough or comfortable enough to know

how to readily develop their budding friendship. They are drawn together by

common experience and vaguely similar character traits such as professionalism

and belief in principle, yet they are divided by other vaguely similar traits

such as independence and pride.

In the end, after a perfunctory

and polite exchange of good-byes, Gillespie, upon reflection, appears to offer

not just respect but a sense of gratitude and even warmth as he smiles and

tells Tibbs to take care, a gesture Tibbs is happy to reciprocate.

Each man has been

challenged by the situation and each has derived strength and encouragement

from the presence and actions of the other. Tibbs’s calm reason and deduction were

tested by emotion, prejudice and racism while Gillespie learned to appreciate

the advantages of principle, reason and deduction and to place them above personal

or professional expediency and prejudice. Reason and principle are seen, then,

as superior to rash and emotional judgment and are a means of professional and

social advancement.

There were two sequels,

both significantly less successful than “In the heat of the night”, perhaps

because they focused on plot and crime rather than character development and

conflict focused on social and cultural themes.

In terms of performance, Sidney

Poitier and Rod Steiger are simply superb as the dignified and reasonable Tibbs

and the distressed and even tormented Gillespie. Each endows his character with

humanity and interest and each ensures total audience engagement.

The script and direction

bubble along at considerable pace with wonderful characterisation and tremendous

atmosphere, using the murder plot as a context for sometimes explosive conflict

and character development.

Special credit should go

to Quincy Jones for his music, especially the catchy and oh-so memorable theme

song.

At times deliberately

uncomfortable to watch, this is a gripping, entertaining and thought-provoking

film that delivers with every viewing.

My thanks for taking the

time to read this article. I hope you found it of some value.

Stuart Fernie (stuartfernie@yahoo.co.uk)